1. INTRODUCCTION: THE BORDER AS RAISON D’ÊTRE1

Abbreviations used: ASVe = Archivio di Stato di Venezia; MC = Maggior Consiglio; SEA = Savi ed esecutori alle acque.

⌅The monastic body referred to in the title is made up of men and physical spaces: on the one hand, the community formed by the monks, the lay-brothers and all those who have a constant and organised relationship with the community; on the other, the monastic spaces —church, cloister, dormitory, refectory— together with the spaces that make up the community’s lands. Physical spaces were crucial to the survival and longevity of these groups of religious men and women. According to the Rule of Benedict, which by the ninth century at the latest had spread widely throughout the Latin Christendom, there could be no monastic community without stabilitas. First and foremost, it consisted in the stable residence of the brothers within buildings such as the oratory, the refectory, the dormitory, that were, intended to make the community able to function by accommodating the various daily activities of the monks.2Letizia Pani Ermini, ed., Gli spazi della vita comunitaria. Atti del Convegno internazionale di studio, Roma-Subiaco, 8-10 giugno 2015 (Spoleto: Centro Italiano di Studi sull’alto Medioevo, 2016); Federico Marazzi, Le città dei monaci. Storia degli spazi che avvicinano a Dio (Milan: Jaca Book, 2015); Michel Lauwers, ed., Monastères et espace social: genèse et transformation d’un système de lieux dans l’Occident médiéval (Turnhout: Brepols, 2014); Peter Klein, ed., Der mittelalterliche Kreuzgang: Architektur, Funktion und Programm (Regensburg: Schnell und Steiner, 2004). Land ownership and the related revenue were, together with the cloister, the other bulwark of Benedictine stabilitas, a guarantee of survival and perhaps prosperity for people who had to live in confinement; the efforts to determine, as clearly as possible, the boundaries of the lands on which property rights and the exploitation of resources were exercised are a constitutive element of the history of every medieval monastery. In environments —be they mountainous or somewhere between land and sea, such as the ones we are concerned with in this study— where land ownership was for the most part pulverised between often competing subjects, we are struck by those communities that endeavoured to establish real physical boundaries marking the space for the inclusion of members of the community and its land prerogatives, and the exclusion of outsiders who could not use its resources.

Often unstable and even more often a point of contention, the internal and surrounding borders of the monasteries we are considering are an example of the enormous variety of frontier experiences which historians of the Middle Ages have grappled with for a long time. When discussing frontiers, we do not just mean land, but also religion, languages, social organisations, economic practices and mental constructs: a complex concept that can be analysed on a macro or micro scale.3David Abulafia, «Introduction. Seven Types of Ambiguity, c. 1100 - c. 1500», in MedievalFrontiers. Concepts and Practices, ed. David Abulafia and Nora Berend (Burlington: Ashgate, 2002); Giles Constable, «Frontiers in the Middle Ages», in Frontiers in the Middle Ages. Proceedings of the Third European Congress of Medieval Studies (Jyväskylä, 10-14 June 2003), ed. Outi Merisalo and Pahta Paivi (Louvain-la-Neuve: Fédération Internationale des Instituts d’Études Médiévales, 2006). Borders should be considered «not simply as a place but as a set of attitudes, conditions, and relationships»;4Abulafia, «Introduction», 27. in this sense the approach and methodology developed by the studies on medieval borders can also be applied in micro scales and for anciently populated geographical areas.

Even religious communities, which were, as is well known, corporate groups and functioned as monastic bodies, contributed to the process of the definition of limits, playing a decisive role in border areas which they helped to colonize through their settlements.5While, as is well known, the role of the monks played in this process in the early Middle Ages has been much studied, it is only recently that we have begun to study the experiences of the border and frontier of monastic communities in the high and later Middle Ages, a hitherto less considered but extremely interesting era: Emilia Jamroziak and Karen Stöber, eds., Monasteries on the Borders of Medieval Europe. Conflict and Cultural Interaction (Turnohout: Brepols, 2014); Emilia Jamroziak, Survival and Success on Medieval Borders, Cistercian Houses in Medieval Scotland and Pomerania from the Twelfth to the Late Fourteenth Century (Turnhout: Brepols, 2011). The production of borders was not limited to their collocation in frontier regions in a geopolitical sense, but also to those situations, which we consider here, when they were placed within populated territories which already featured seigniorial or communal political organisms, however unstable in their geographical structures and dimensions. The areas in which these monasteries were located were frontier areas themselves even though their location was within regions of ancient settlement; the borders progressively marked (between landowners, institutions, new settlers, etc.) were typically unstable and required constant redefinition. There were hardly landowners in these areas, and yet they saw diverse economic and political interests on the part of potential laic and ecclesiastic owners, both public and private, benefactors of one or another religious foundation. Therefore, in these contexts, competition could be fierce, and borders defined by these communities could constitute a zone of productive economic and social interaction, but also of violence. Monks were a crucial element in the negotiation of space and in the balance of local powers even in these contexts.

The relationship of these monastic bodies with the land was fluid and changeable over time and space. Land is both a material and a resource, it has economic significance, it can be sold, exchanged, rented, but it can also be invested with cultural, emotional, and symbolic meanings. The territorial body that delimits itself within the monastic confines incorporates spaces and lands that are easily granted, naturally affording clear and explicit material signs of their spatial projection (rivers, trees, stones). The marking of the land does not, however, eliminate pre-existing relationships, such as intermingling of use, traditions, and popular sentiments, which can generate conflict and establish, at the same time, different degrees of mutually exclusive territorial relations.6Andrea Pase, Linee sulla terra. Confini politici e limiti fondiari in Africa subsahariana (Rome: Carocci, 2011), 47-50. On borders as a manifestation of territorialisation processes, seen not as dividing lines but as social practices involving multiple dimensions (economic, cultural, political): Anssi Paasi, «Deconstructing Regions: Notes on the Scale of Spatial Life», Environment and Planning 23 (1991): 239-256, https://doi.org/10.1068/a230239.

The act of establishing a border, which was both material and cultural, had complex implications; it was a significant statement of separation, difference, and community.7Megan Cassidy-Welch, Monastic Spaces and Their Meanings. Thirteenth-Century English Cistercian Monasteries (Turnhout: Brepols, 2001), 25. Borders remarked legitimate ownership of the land, symbolically reminded the separation between the laic and religious worlds and guaranteed protection for the inhabitants of the cloister from the outside world. The act of borders was a semiotic system, which had to be understood precisely as a system.8Luciano Lagazzi, «I segni sulla terra. Sistemi di confinazione e di misurazione dei boschi nell’alto medioevo», in Il bosco nel medioevo, ed. Bruno Andreolli and Massimo Montanari (Bologna: Clueb, 1990), 18, with a reference to Umberto Eco. The process of delimitation involved a manipulation of the environment, a new, specific semantisation of elements such as trees, stones, and waterways, as a result of which they took on terminal value.9Giampaolo Francesconi and Francesco Salvestrini, «La scrittura del confine nell’Italia comunale: modelli e funzioni», in Frontiers in the Middle Ages. Proceedings of the Third European Congress of Medieval Studies (Jyväskylä, 10-14 June 2003), ed. Outi Merisalo and Pahta Paivi (Louvain-la-Neuve: Fédération Internationale des Instituts d’Études Médiévales, 2006), 11. These operations of border definition can be defined as «verbal mapping»: «where the limits of particular properties were described in terms of known landmarks»: Constable, «Frontiers», 9. The next step was a legal agreement granted by a notary with publica fides that sanctioned the patrimonial value of the boundary map. Such a boundary map became a vehicle for precise information regarding the usability of the space and resources covered within those terms. The mismatch of the boundaries on the land with those described by the notaries could in fact be sufficient to invalidate the property rights of a plot of land.10We have an example of this in a deed of 1287 from the Cistercian Abbey of Chiaravalle Milanese; the abbey obtained full ownership of a plot of land in court because the other party presented title deeds in which boundary elements were indicated that had not been found on the land: Ada Grossi, ed., Le carte del monastero di Santa Maria di Chiaravalle, vol. 2, 1165-1200 (Pavia: Università degli Studi di Pavia, 2008), no. 123.

Establishing boundaries is an act of authority, and physically marking the ground is its visual representation. When analysing operations regarding boundaries and their reconfiguration, power relations and economic relations emerge between private individuals, monastic and lay owners, and public powers that sought to establish, draw, and renew lines on land, as well as on water, in order to define private property; but at the same time, the process of learning emerges, which is awareness and knowledge of the land and all the elements that shape it, both anthropic and non-anthropic in kind. The terminal use of toponyms and anthroponyms means that the boundary becomes the distinguishing element between known and recognisable territory and unknown territory.11Jamroziak, Survival and Success, 11. Constable also mentions the use of natural elements and perambulation in the local border creation process, as well as the importance of a collective memory of these borders (Constable, «Frontiers», 9-12). Indeed, shaping through borders entails an ever-deeper knowledge of the environment one wishes to define. In some cases, this knowledge came to materialise in a process of personification of both the environment and the boundary itself, where the boundary sign became the actual producer.12Reference is made to the - so far unique - case of some ninth-tenth century boundary stones, found in the territory of Verona and used to delimit a wood belonging to the large urban abbey of San Zeno. The wording of the text of the boundary stones presupposes the personification of the boundary sign, which ‘speaks’ in the first person; cf. Fabio Saggioro, Paesaggi di pianura. Trasformazioni del popolamento tra età romana e medioevo. Insediamento, società e ambiente tra Mantova e Verona (Florence: All’insegna del Giglio, 2010).

This learning process emerges very clearly from the documentation we have examined, characterised by its common monastic origin, despite its geographical and chronological variety. These documents are notarial deeds, chronicles, and legal sources, kept in monastic archives, which record the memory of the communities we are dealing with and allow us to reconstruct the mental and material processes that led the monks to define their boundaries. The monastic bodies were distributed over a vast area of northern Italy.

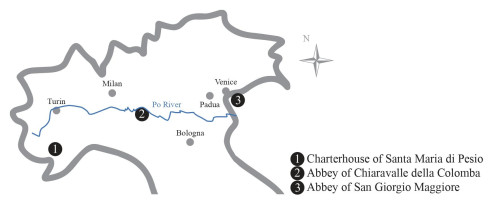

We will start from the north-west, from the mid-mountains of Piedmont, subsequently passing south of the river Po through the Emilia-Romagna plain, moving East, towards the Adriatic coast, along the final stretch of land characterised by a strip of freshwater, brackish lands and marshes overlooking the Venice lagoon (fig. 1). The comparison of such diverse and distant environments gains importance in the light of an easy-to-overlook idea, even if it is common to different periods and areas: the creation of the border was always qualified as a vast operation of overall representation, an exercise that involved different actors interested in the interplay of borders on land. In this network of interests, which was created around the boundary operations, the public also played an important role, alongside private individuals, which made it a testing ground for the territorial and political assertion of a superior and coordinating power. This dynamic is particularly visible in the area of the Gronda Veneta and the shore of the Venetian mainland, i.e. the marshy plain that overlooked the Venetian lagoon, whose productive, and hence strategic, nature due to the strong presence of uncultivated land, made it a centre of interest for the Venetian Republic from the fifteenth century onwards, through the determination of inclusive and exclusive borders and more fluid boundary lines. The documentation of the monastic communities forms the basis of our research. The first community is the Carthusian house of Pesio in Piedmont, whose documentation was collected and published by local scholars at the beginning of the last century, thus saving it from dispersion. We have also analysed the original documents of the Abbey of Chiaravalle della Colomba, some of which were published in the seventeenth century. This archive is noteworthy due to its variety of documents, both in terms of quantity and type. The documentation examined for the Venetian area consists largely of unpublished medieval documents that are part of complex court dossiers. These dossiers comprise a large amount of heterogeneous documentation related to the Abbey of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice throughout the centuries, from the thirteenth to the eighteenth. The documentation comprises drawings, private writings concerning the creation of maps, registers with measurements of the lands owned by the monastery, accounting books, and files of duplicated documents created by the magistracies. The covers of the court files are frequently labelled Carte ad lites. The court files in this case contain all the documentation collected during disputes over the monastery’s property. This includes disputes where the monastery was the direct owner or where the property in question bordered its own.

Fig. 1. Northern Italy. From West to East: Certosa di Santa Maria di Chiusa Pesio (Cuneo) in Piedmont; Abbey of Chiaravalle della Colomba, in Alseno (Piacenza) in Emilia-Romagna; Abbey of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice, Veneto.

2. MOUNTAIN DESERTS: THE CARTHUSIAN BORDERS

⌅Needless to point out that, in the cloister, inclusion and exclusion of people and material goods were largely permeable conditions: monks and hermits more or less frequently left the cloister, outsiders entered it to transact business or for devotion and to benefit from the monks’ prayers, or to take possession of the monastic resources by force. And then there were the conversi, members of the communities engaged in land administration; for this very reason, they were authorised to cross the monastic boundaries continually in both directions, the dividing line between the century and the circumscribed space in which that particular religious experience was to take place. This circumscribed space was the physical dimension in which the monastic families of the Carthusians and Cistercians established a new relationship with their environment with respect to the past. For them, solitude, the primarily mental space that the Church Fathers called desertum, was no longer an inner, individual state of spiritual isolation. The myth of the desert represented values that were the opposite to those of the city; it was simultaneously the place of temptation and the place of heroic asceticism for those monks who desired to move closer to God. The deserts of the Fathers of fourth century monasticism then paradoxically returned, in the booming West, to be defined as real empty space, or rather: occupied exclusively by the monastic community. It is interesting to note that in regions where there were no deserts in the strict sense, these spaces took on both a theological and ideological significance, justifying the existence of these religious groups in relation to historical and social conditions.13Catalin Taranu, «A New Heaven and a New Earth. The Making of the Cistercian Desert», Ex historia 5 (2013): 1-18; Richard E. Sullivan, «The Medieval Monk as Frontiersman», in Christian Missionary Activity in the Early Middle Ages (Aldershot: Variorum, 1994), no. VI; Benedicta Ward, «The Desert Myth. Reflections on the Desert Ideal in Early Cistercian Monasticism», in Signs and Wonders. Saints, Miracles and Prayers from the Fourth Century to the Fourteenth (Aldershot: Variorum, 1992), 183-199. Cistercian monks and Carthusian hermits consciously sought to artificially recreate a veritable desert, by means of the establishment of boundary markers carefully identified in the founding charters of the communities themselves and reiterated whenever it was convenient. And they did not only seek isolation in the forests of Western Europe but, as we shall see in a moment, conceived the practice of desert life even in the midst of the villages and populous communities of the Po Valley. These men were hermits who wanted to live in isolation, but they also conceived of themselves as pioneers, committed to transforming the wilderness —even when it was not wilderness— under the banner of rationality, bringing in monastic norms; in particular, they drew boundaries, which gave the wilderness its shape and structure.

Let us first see how Carthusian monks created their own space of isolation from the world in the twelfth century: something far more tangible than the inner solitude shared with their brethren, a material condition that was often assured by the presence of woods, the desert par excellence of the West.14Anne Wagner and Monique Goullet, «La forêt dans l’hagiographie», in La forêt au Moyen Âge, ed. Sylvie Bépoix and Richard Hervé (Paris: Le Belles Lettres, 2019), 85. For their settlements, they envisaged the scrupulous delimitation of an area surrounding the monastic buildings, defined by precisely identified boundaries, which had to be completely uninhabited. No person, male or female, from outside the community could cross its boundaries, but neither could the hermits leave it. This was their desertum, within which the communities’ land expansion was also to take place.15Cf. Jacques Dubois, Histoire monastique en France au XIIe siècle. Les institutions monastiques et leur évolution (London: Variorum Reprints, 1982), 186-197. There was often a certain discrepancy between what the Carthusian Consuetudines envisaged and what the concrete and contingent situations of land and agricultural arrangements allowed, similar to what we have already seen with the other great reformed order, the Cistercians. Cf. Rinaldo Comba, «La prima irradiazione certosina in Italia (fine XI secolo - inizi XIV)», Annali di storia pavese 25 (1997): 17-36; Sylvan Excoffon, «Aspects et limites de l’expansion temporelle cartusienne. La Grande-Chartreuse et les chartreuses dauphinoises aux XIIe et XIIIe siècle», in Certosini e cistercensi in Italia (secoli XII-XV), eds. Rinaldo Comba and Grado Giovanni Merlo (Cuneo: Società per gli Studi Storici, Archeologici ed Artistici della provincia di Cuneo, 2000). Only the conversi, subject to a regime that differed profoundly from that of the hermits, were authorised to cross the borders in both directions to take care of the administration of the estate. This artificially carved out portions of land between villages, pastures, and forests, assuming a precise juridical value that ensured its inhabitants the exclusive use of the resources it contained. In several cases, the implementation of this process triggered a strong conflict with the local communities, which were attacked and often overwhelmed by a form of land expansion that was particularly dangerous for the stability of the local economy when it was characterised by a search for separateness.16Paola Guglielmotti, «La costruzione della memoria di Santa Maria di Pesio: vicende proprietarie e coscienza certosina nella cronaca quattrocentesca del Priore Stefano di Crivolo», in Certose di montagna, certose di pianura. VIII centenario della certosa di Monte Benedetto, ed. Silvio Chiaberto (Borgone Susa: Melli, 2002), 311-328.

The Carthusian monastery of Pesio was founded in 117317Paola Guglielmotti, «Gli esordi della certosa di Pesio (1173-1250): un modello di attività monastica medievale», Bollettino storico-bibliografico subalpino 84 (1986): 5-9; Guglielmotti, «La costruzione della memoria». at an altitude of about 850 metres in the mountains of southern Piedmont, endowed with a set of properties that occupied the highest part of the Pesio valley.18Paola Guglielmotti, I signori di Morozzo nei secoli X-XIV: un percorso politico del Piemonte meridionale (Turin: Deputazione Subalpina di Storia Patria, 1990). It was in the deed of foundation that the boundaries of the lands were defined, which, from that moment on, were to constitute both the main core of the landed estate and the desertum within which the institution was based. As the notary Giordano wrote, that land —cultivated, uncultivated and wooded— was «between the mountains of the village called Chiusa, in the place called Arda, from the Alma stream and the Corverio stream to the top of the alpine pastures, along both banks of the river that is called Pesio».19«In montanis ville que dicitur Clusa, sita in loco qui dicitur Ardua, a rivo de Alma et a rivo Corverii usque ad summitatem alpium, ex utraque parte fluvii qui dicitur Pesio»: Biagio Caranti, La certosa di Pesio. Storia illustrata e documentata (Turin: Camilla e Bertolero di Natale Bertolero, 1900), 1:3-4. The boundary markers used by the notary were therefore the watercourses in the area, pastures, mountain meadows and forests, but also artificial structures such as roads, chapels, buildings of production (batenderia), and others for care of the infirm (infirmaria).20Caranti, La certosa di Pesio, 1:21-22. It was a mountainous area, in which there were sive culta sive inculta lands (‘both cultivated and uncultivated’) and forests (those typical of the middle and high mountains, with a predominance of conifers and broad-leaved trees and probably with a preponderance of oaks). This news comes from a later source, a fifteenth century chronicle narrating the history of Pesio, according to its author Stefano de Crivolo, who was its prior, the alpes, mountain land belonging to Pesio, were covered with «forests of firs and other species […] in which there is a large and innumerable quantity of firs».21Caranti, La certosa di Pesio, 2:18-19. The wooded landscape of firs, oaks and beeches, described in the following lines, must not have been radically changed from two centuries earlier, at the time of its foundation, although it may have been affected by human presence and activities. Furthermore, the other montes, that is, mountain pastures, of the surroundings were characterised by the abundance of trees and the variety of tree species, among which were oaks and beeches.

Of course, the attention devoted by the chronicler to the description of the Carthusian forests was consistent with the tangible economic interests in the exploitation of this resource: first of all, at the foot of the mountain there was at least one sawmill fed by the forests themselves, which produced wood for carpentry and, habundanter (i.e. in large quantities), planks and boards for various uses.22Caranti, La certosa di Pesio, 2:18-19: «Resica que laborabat […] de arboribus prefatis […] pro edificiis, assidibus seu postibus fiendis». But of equal importance must have been the consideration of the symbolic value, as well as the economic value, of the nemora infinita of Pesio, a veritable bulwark and desert where the hermits fulfilled their mission as ascetics and pioneers. This also explains the prior’s unusual attention to the quality of the forests, which testified to their good health, among other things. It should also not be overlooked that the territory to which the Carthusians —being the true pioneers they felt they were— gave shape through the act of drawing its boundaries, was the object of another conquest implemented through the modification of toponymy. It was not enough to establish that dividing line between inclusion and exclusion, it was also necessary to give structure to what lay within that line. Giving a (new) name to streams, meadows and mountain pastures is the most concrete way of taking possession of them and claiming the exclusive right to exploit them.23Cf.Guglielmotti, «La costruzione della memoria», 36-37.

The area in which they settled was thus anything but void of human presence, as evidenced first and foremost by the abundance of place names and micro-toponyms, as well as the existence of non-temporary constructions; a situation that was a harbinger of confusion between the rights of the different parties involved. The boundaries were also materially discontinuous; the boundary made up of lines that only materialised when travelling from one point to the next was characteristic of wooded and marshy land, i.e. what is known as «productive uncultivated land». This characteristic left room for a wide use of the demarcated territories, whether legalised or not,24Lagazzi, «I segni sulla terra», 20. but was also a source of confusion and ambiguity in the definition of extractive rights. One can understand how easily a heated conflict over usufruct rights could arise, involving coenobia, peasant communities, large and medium-sized landowners. The Carthusian house in Piedmont, from this point of view, was an exemplary case,25See the reconstruction of the long season of conflicts in Guglielmotti, «La costruzione della memoria», 39-52. but another very well-known example of the conflict provoked by the spread of new monastic settlements, this time Cistercian, is attested in the 1220s and 1230s by Walter Map in his famous text De nugis curialium (‘Courtiers’ Trifles’), in reference to the white monks operating on English soil.26On this author and his literary production, see most recently Stephen Gordon, «Parody, Sarcasm, and Invective in the Nugae of Walter Map», The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 116, no. 1 (2017): 82-107.

Some forty years after its birth, in 1218, the Pesio desert was redisplaced by the hermits through a new boundary operation that radically changed its appearance and significantly increased its size, extending it from the mountain towards the plain.27Caranti, La certosa di Pesio, 1:21-22. This second operation, due to its thoroughness, was even more radical than the first in its desire to oust anyone, and thus also the peasants of neighbouring villages, from the new Carthusian territorial body. In this second case, rather than signs with a terminal character in the proper sense, natural elements were mostly —but not exclusively— used, centred around the territorial water and road systems of the area.28Lagazzi, «I segni sulla terra», 19.

In order to underscore the nature of this veritable desert —empty or emptied of human presence— it must be said that the Carthusian visitatores, entrusted with the task of drawing the new, much larger boundaries, took care that no villages, castles or other houses were to be found within them. Similarly worthy of note is the knowledge of places (waterways, micro-toponyms, country roads, presence of productive buildings, mountain pastures, etc.) that made it possible to achieve that degree of detail. The document’s authors do not appear to have been technicians, that is, professionals skilled in the techniques of surveying, i.e. with the ability to carry out planimetric surveys and land surveying, but they were certainly assisted by locals. Reasons for this second demanding operation of boundary redrawing included the presumed survival necessities of the hermits who, limited within the confines of 1173, declared that they could only derive sufficient resources to support themselves for six months of the year.29On this deed see also Franco Panero, «Terra certosina e terra cistercense», in Certosini e cistercensi in Italia (secoli XII-XV), ed. Rinaldo Comba and Grado Giovanni Merlo (Cuneo: Società per gli Studi Storici, Archeologici ed Artistici della provincia di Cuneo, 2000), 345. An alpine desert that had become too small was redesigned and expanded from its original core by extending it towards the plains, while the process of excluding the inhabitants of neighbouring villages became more impressive and widespread.

3. A DESERT ON THE PLAINS: THE CISTERCIANS OF CHIARAVALLE DELLA COLOMBA

⌅The Cistercian monks became notable, between the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, for their ability to value and control both physical space and the faithful. While adopting the rule of Benedict, they shared with the Carthusians a nostalgia for the desertum and ascetic isolation. And while for most of their houses this nostalgia only took the form of an attempt —prescribed by the rules of the order and nevertheless often falling short— to settle far from people and their settlements, there were a few interesting exceptions in which a simulacrum of the desert seemed to be artificially created.

Chiaravalle della Colomba, founded in 1136 in the countryside near Piacenza, just south of the river Po, is one of these exceptions. At the time of its establishment, Bishop Arduino of Piacenza, together with the consuls of the powerful Commune of Piacenza, who represented the will of the citizens, delimited the perimeter of this new and unusual desert with concrete, albeit general, geographical references. It was a veritable boundary operation agreed upon and planned between the city authorities, both ecclesiastical and secular; the deed of foundation states that, within the space delimited by an imaginary line (which became concrete and operational at that precise moment) that united some villages surrounding the nascent abbey, no church or secular building should be built.30«We add one more thing, which we felt it was important to put in writing, and that is that from the place called Barastalla to Alseno and from Alseno to Fiorenzuola and from Fiorenzuola to Borio, no church or secular building is built»: Pier Maria Campi, Dell’historia ecclesiastica di Piacenza (Piacenza: Per Giovanni Bazachi Stampatore Camerale, 1651), 1:537-538, where the text of the founding act of Colomba by Bishop Arduino can be found.

In this way, a buffer zone was artificially created in the heart of a fertile plain teeming with villages and landed estates; a desert from which, if the inhabitants had not been displaced already, the conditions were created for its depopulation, freezing the settlement pattern and preventing the construction of any new buildings.31Several authors observe, with reference to the Cistercians, that «the strategies used to cut themselves off from the secular world created tensions with the local population. The locations chosen by the Cistercians and their benefactors were sometimes deserts in name only»: Gordon, «Parody, Sarcasm, and Invective», 97. In this case the desertum, rather than being a precondition for the new foundation, probably became its result; it was such an ambitious and difficult project that the Colomba monks and all their benefactors were driven by a veritable «optimism of will».

The boundary and the isolation were further consolidated through subsequent concessions by emperors and popes, in which they reiterated the ban on building new buildings within the boundaries «drawn in a special way» —so say the foundation documents— by Bishop Arduino, the clergy and the citizens of Piacenza.32Campi, Dell’historia ecclesiastica, 538. The text states that the boundaries were considered «specialiter designatos» by the city authorities. This is one of the examples of the direct involvement of the public in boundary operations of certain private properties considered particularly important for the communities concerned with them. These operations were by their very nature extremely delicate, due to the relevance of the economic and political interests of the parties involved.

4. MEASURING AND REDEFINING UNSTABLE LAGOON TERRITORIES

⌅For Pesio and Chiaravalle, geographically located on solid land, boundary activities involved the accurate description of the physical and material limits within which the environment for recreating the desertum was to be demarcated. In contrast, for the Venetian monasteries, it was a matter of drawing the limits and distances on liquid, fluctuating, shifting terrain, both in environmental and jurisdictional terms. It was therefore an even more delicate operation, susceptible to dispute by the inhabitants of the area due to the extreme instability of this mix of land and water, which opened the way to endless disputes. In the organisation of the monastic context in the lagoon, space on the water was sometimes measured, from island to island, in order to understand whether the land was at an adequate distance to host communities affiliated to the same congregation. Indeed, in the 1330s the Cistercian monks of San Tommaso dei Borgognoni opposed the foundation of new communities of nuns in the lagoon by appealing to a statute of the order that imposed a distance of at least one league between female and male communities.33The request of the nunnery of St Matthew, established in 1218 on the lagoon island of Constanziaco, to be incorporated in the Cistercian Order some fifteen years later was opposed by the abbot of the neighbouring male Abbey of San Tommaso dei Borgognoni, who complained that the distance between the two houses was insufficient; a distance that had been set by the order since 1152, cf. Mathieu Arnoux, Un monde sans ressources. Besoin et société en Europe (XIe-XIVe siècles) (Paris: Albin Michel, 2023), 138-139. The issue was resolved in favour of the nuns thanks to the intervention of Pope Gregory IX: Lina Frizziero, ed., S. Maffio di Mazzorbo e Santa Margherita di Torcello (Firenze: Leo Olschki, 1965), 25, no. 74-76. Since the beginning of the thirteenth century, the establishment of any new Cistercian house had to be approved by the abbots and the incorporation procedure was triggered by a petitio sent to the General Chapter of the Order. The General Chapter would appoint a commission of two —or more commonly three— abbots to investigate the location to assess whether the area was adequate and suitable for the new settlement, cf. Guido Cariboni, «Il monachesimo cistercense femminile in Lombardia e in Emilia nel XIII secolo. Una anomalia giuridico istituzionale», in Il monastero di Rifreddo e il monachesimo cistercense femminile nell’Italia occidentale (secoli XII-XIV), ed. Rinaldo Comba (Cuneo: Società per gli Studi Storici, Archeologici ed Artistici della provincia di Cuneo, 1999), 38-39. The assessment of the favourable conditions for the foundation of new Cistercian nunneries is a common practice in northern Italy, which is widely attested. However, the peculiarities of the Lagoon required the application of special procedures to evaluate the specific case.

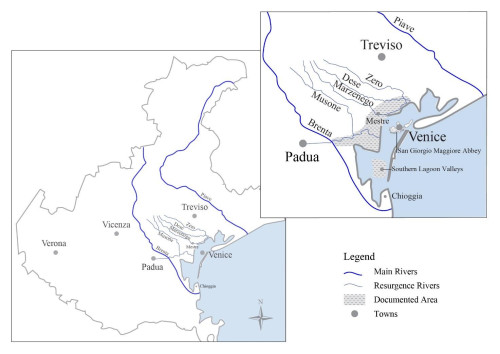

The geographical space within which the territorial and environmental dynamics we will now discuss coincides with the lagoon territory itself, made up of islands and territories that periodically emerge from the water, but it also extends along the arc of the first mainland that overlooks the waters of the Venetian lagoon: a low plain, that remained sparsely populated until the beginning of the fifteenth century; it was characterised by large expanses of uncultivated land and which in the expansive period (demographically and economically) in the second half of the fifteenth century began to realise its enormous potential (fig. 2). Along this marshy plain, as early as the tenth century, the first land expansion of the great Venetian abbeys took place, which exploited large areas of uncultivated land and extensive areas of woodland to obtain primary resources.34These themes have been addressed once more by Dario Canzian, «I boschi della Repubblica di Venezia tra terraferma e laguna (XII-XIII secolo)», in Selve oscure e alberi strani. I boschi nell’Italia di Dante, ed. Paolo Grillo (Rome: Viella, 2022), 144-150. This arc that runs between the lagoon and the mainland, called the Gronda Veneta, was an amphibious environment that was constantly subject to major changes. In the short term, these changes were mainly caused by the waters of the rivers,35In addition to the main rivers coming from the Alpine areas, such as the Brenta and Piave, the investigated area is furrowed by the course of resurgence rivers, i.e. watercourses of «underground» origin characterised by the accentuated meandering of their riverbeds. Cf.fig. 2. which, in their final stretch, crossed a plain that in many areas was below sea level, ending up in a tangle of branches, marshes and coastal lakes. In the long term, the transformations of this environment depended on changes in sea level (marine transgressions and regressions) and the phenomenon of coastal land subsidence, resulting in the swamping of vast areas.36See Wladimiro Dorigo, Venezie sepolte nella terra del Piave. Duemila anni fra il dolce e il salso (Rome: Viella, 1994), 2-8. The phenomenon of soil subsidence and the consequent swamping and dulcificazione (i.e. ‘intrusion of freshwater’) of vast lagoon and peripheral lagoon areas was one of the most problematic issues that the Venetian government had to deal with as early as the fifteenth century, entrusting well-known hydraulic engineers with the task of studying the territory and proposing solutions. Right from the start, the importance of drastically intervening by moving the terminal rods of the rivers flowing into the Venetian lagoon outside or away from the lagoon territory was recognised. Regarding the issues of safeguarding the Venetian lagoon system, see Bernardino Zendrini, Memorie storiche dello stato antico e moderno delle lagune di Venezia e di que’ fiumi che restano divertiti per la conservazione delle medesime (Padua: Nella stamperia del Seminario, 1811); Giuseppe Pavanello, ed., Antichi scrittori di idraulica veneta. Marco Cornaro (1412-1464) (Venice: Ferrari, 1919), (Scritture sulla laguna, I). The ecological viscosity of this brackish environment, halfway between the land and the sea, has historically required, on the part of both the public and private sectors, a constant activity of control, description, and redefinition of property boundary limits. These uninterrupted operations of knowledge and description of «unstable» places, subject to water invasion, have given rise since the Middle Ages to a series of writings and graphic representations concerning the boundaries of both public and private property.

Fig. 2. The Zero, Dese, Marzenego and Musone-Bottenigo waterways.

Through ancient maps and charts, which testify to the original boundaries and boundary signs (stones, poles, etc.), an attempt was made to recover old property rights that had been jeopardised first and foremost by the element of «water»:: the fresh water of the rivers, which with its floods and diversions (natural or artificial) submerged and redesigned the land, the brackish or marine water that, lapping the land, established its legal ownership and possession de iure singuli or de iure universorum.37Findings are known «super aquarum qualitate» to establish the salinity of water: cf. Stefano Barbacetto, «La più gelosa delle pubbliche regalie»: i beni «communali» della Repubblica veneta tra dominio della Signoria e diritti della comunità (secc. XV-XVIII) (Venice: Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, 2007), 9. Hence, water contributed to establishing the legal status of land: the proximity of the salt waters of the sea versus the fresh waters of the lagoon thus determined the public or private status of land. The difficulty in determining the nature of properties that fell within the boundaries of the Venetian dogado38The territory of the dogado consisted of a strip of land and lagoons that stretched between the towns of Grado and Cavarzere, the northern and southern extremes of this strip. Whereas, on the mainland side, the border was defined in the Pactum Lotharii (840); on the problems of interpretation raised by the Pactum including with reference to the borders of the duchy cf. Stefano Gasparri, «Anno 713. La leggenda di Paulicio e le origini di Venezia», in Venezia. I giorni della storia, ed. Uwe Israel (Venice: Centro Tedesco di Studi Veneziani, 2011), 33-35. fostered the emergence of the Super publicis office on the seventh of July 1282 and the creation, some months later, of the Giudici del Piovego: experts in charge of establishing the private or public essence of the assets and, consequently, of settling any disputes or misappropriations.39The Super publicis office, together with the other three existing magistracies of the Super patarinis et usurariis, Super canales rivos et piscinas, Super pontibus et viis civitatis Rivoalti, came together in the larger Ufficio dei Giudici del Piovego: cf. Silvano Avanzi, Il regime giuridico della laguna di Venezia. Dalla storia all’attualità (Venice: Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, 1993), 62. The work of the judiciary was essentially based on the notion that the public nature of the marshlands derived not only from their objective natural characteristics, but also from the particular practices of utilisation traditionally conducted on those places and assets.40This included the judges’ recourse to the testimony of the inhabitants or those who frequented the place under investigation (workers, fishermen, users…) to verify the conformity of the use of the property: Bianca Lanfranchi Strina, ed., Codex Publicorum (Codice del Piovego) (Venice: Fonti per la Storia di Venezia, 1985), 17-18. It goes without saying that such a survey of property rights over lagoon and surrounding lands and waters today gives scholars a kind of snapshot of the territory and rights exercised over marginal lands in the period between the end of the thirteenth century and the fourteenth century.41«The establishment of the judiciary […] constituted a far-reaching political intervention, with considerable social and patrimonial repercussions, which engaged the court for decades»: Lidia Fersuoch, Codex publicorum. Atlante. Da San Martino in Strada a San Leonardo in Fossa Mala (Venice: Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, 2016), 4. Throughout the documentation of the judiciary, there are frequent references to the monasteries in the lagoon, obviously having played a role in property disputes and the misappropriation of portions of public land and water. They took an active part in these dynamics, so much so that in 1353, the Maggior Consiglio decreed that de Pubblicis officials should undertake a reconnaissance and lay out the divisions of waters, lands and marshes, describing the new limits that were placed on them. They also had to delimit the boundaries per signa (i.e. with boundary marks: stakes, stones, trees) so that those divisions were known to everyone, in order to avoid further usurpations in the future by private individuals, monastic communities and churches on the lands and waters belonging to the Duchy.42ASVe, SEA, 331, 1350, 15 April, in MC, f. 87r.

The need to redefine the limits of many properties in the lagoon and surrounding areas («aquae, terre, et paludes») became more frequently documented in the monastic sources of the late fifteenth century. Indeed, it was at this time that the properties became the object of new and extensive boundary surveys, associated with precise topographical mapping activities commissioned by the representatives of the monastic communities themselves and aimed at ascertaining or redefining old and new property limits. The written testimonies of these operations of knowledge and reorganisation of the space outside the cloister flowed into registers and land registries, thus increasing the quantitative and qualitative value of the monastic documentation of the late fifteenth century.43On these topics see Alessandra Minotto, «Tra le carte dei monaci. Mappe, disegni, strumenti e tecniche per il rilievo topografico del territorio veneziano». Ateneo Veneto 14, no. 2 (2015): 37-61. The increase in documentation of property also responds to the need to adapt to the redecimazione, a census of estates and rents collected and paid, in essence the property owned by monasteries and convents, which from 1462 were also subject to taxation: Ludovica Galeazzo, «Autorità ecclesiastica e civile nell’iconografia dell’arcipelago veneziano tra XVI e XVII secolo», IN_BO. Ricerche e progetti per il territorio, la città e l’architettura 12, no. 16 (2021): 189, https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.2036-1602/13130. The description of the borders and everything inside and outside them had to be accurate, therefore, the commissioning of these works had to be entrusted to experts and surveyors (perticatori), as some interesting documents concerning the Venetian monastery of San Giorgio Maggiore show.44Reference is made to the measurement of «perch» booklets in the monastic collections, in which a series of topographical surveys of areas belonging to the monastery’s land can be found. In them, the boundaries and composition of the property are described in great detail; cf.Minotto, «Tra le carte dei monaci», 43-52. Indeed, around the 1560s, the abbot recruited two experts, including a hydraulic engineer, Antonio da Piacenza,45The names of the two experts mentioned in the documentation are Michele da Asigliano and Antonio da Piacenza. The latter is mentioned by one of the most important writers on Veneto hydraulics, Marco Cornaro, for having taken part as an engineer in 1457 in a commission of Water Saviours, to which the following were added «engineers, seafarers and fishermen, practical men». This commission was charged with examining the course of the river Brenta and other waterways in order to solve the long-standing problem of the silting up of the Venice lagoon: cf.Pavanello, Antichi scrittori, 96-98. in order to describe numerous wooded and grassland properties located in the vicinity of Mestre,46Sixteenth-century surveys of the Mestre podesteria reveal that convents and monasteries, particularly those in Venice, were among the primary beneficiaries of the land wealth of the clergy. Especially in the localities closest to the lagoon, the monastic communities controlled 89,6 % of the land area, which was subdivided into medium-large farms; Maria Grazia Biscaro, Mestre. Paesaggio agrario, proprietà e conduzione di una podesteria nella prima metà del XVI secolo (Treviso: Canova, 1999), 62. along the road «que venit Mestre et vadit Paduam»,47Given the complex of water and land routes that connected Padua to Venice in the medieval period, and considering the places where the measurements were taken, we hypothesis that the route mentioned here may have been connected to the Naviglio Brenta waterway, the well-known Riviera del Brenta, passing through Mira, Dolo, Stra, Oriago and Malcontenta, connected via the Piovego canal to the city of Padua. On the complex connection between Padua and Venice cf. Remy Simonetti, Da Padova a Venezia nel Medioevo. Terre mobili, confini, conflitti (Rome: Viella, 2009). and became in those years the subject of heated disputes between San Giorgio and other religious and lay communities, who also owned property in the area.48With reference to the presence of numerous booklets of measurements (in perches) preserved in the ancient collection of the Monastery of San Giorgio Maggiore in the State Archives of Venice, it may be hypothesised that San Giorgio had adequate economic resources to invest in the census and accurate description of all its properties, including the work of technicians and topographers of a certain fame. The private recruitment of specialised figures is widely attested for the subsequent period, when esteemed professionals such as engineers and surveyors alternated the public activity of hydraulic engineering with various private consultancies. On this subject cf. Andrea Peressina, «“La gelosa professione” dei pubblici periti agrimensori della magistratura “sopra beni comunali” (1574-1797)», Archivio Veneto 19, no. 6 (2020): 80.

The meticulous surveying work, with detailed descriptions of the area identified, was part of a long-established process consisting of several stages: old and unstable boundary rights were proved by means of old property titles, then redefined by digging new dividing ditches, and finally, the new boundaries were measured and sometimes, if necessary, described in a drawing.49«Only in a few special situations did the technician attach to the sworn report an explanatory «drawing» of the property’s state of affairs, made by him on paper»: Peressina, «La gelosa professione», 84. For example, in a small parchment booklet, Antonio da Piacenza expertly and neatly describes the boundaries of various monastic properties in the Mestre area, mainly wooded plots, alternating with arable land, meadows, marshes and furrowed by waterways,50The wooded cover on the strip bordering the lagoon edge in the Mestre area is well attested and was still extensive in the mid-sixteenth century. In particular, the records list 100 hectares of municipal woodland in the villa in Chirignago and 150 hectares of woodland in the villa in Carpenedo; Biscaro, Mestre. Paesaggio agrario, 26-29. disputed by the nuns of San Zaccaria in Venice. Among the various annotations, he reports that, to put an end to the dispute over those properties, a pit was dug by means of some oxen:

1469 a dì 6 de mazo fo tolto via una differentia la quale era intra el monaster de San Zacharia e el monasterio de San Zorzo in un prato, ultra la via che va a Padua, in su la possessione che ten Menego Guisato, e fo facto uno sorcho cum li boy in lo dicto prato per Guido, fiolo de Menego Guisato, cum volontà de ser Jacomo factore de San Zacharia e del monastero de San Zorzo. […] Presenti li testimoni e mi domino Antonio da Piacenza, lo qual scripsi.51«A dispute was settled between the monastery of San Zaccaria and the monastery of San Giorgio over a meadow beyond the road to Padua and the property managed by Menego Guisato, and a ditch was dug with oxen in the aforementioned meadow by Guido, son of Menego Guisato, with the consent of ser Giacomo, tenant of the monastery of San Zaccaria, and the monastery of San Giorgio. […] Before the witnesses and I, domino Antonio da Piacenza, who wrote»: ASVe, San Giorgio Maggiore, folder 72, trial 148, ff. without markings.

It is then recalled that San Giorgio Maggiore and the Commune of Chirignago agreed to divide a portion of the forest, called «de Campolongo» located not far from the places mentioned above, again by means of ditches: the Campo Longo forest was separated from the municipal forest by the excavation of several pits «da monte e da sera».52ASVe, San Giorgio Maggiore, folder 72, trial 148, ff. without markings. And again, thanks to our expert’s investigation, we learn of the claims made by the men of Chirignago against the community of San Giorgio for the ownership of several plots of woodland located near the canal called Bottenigo. The dispute was resolved thanks to the fact that the monks presented some ancient documents in which, we read in the surveyor’s report, the ownership of the monastery over those lands was so clearly attested that the men of the Commune were forced to abandon their claims forever:

E cusì tutti li homeni infrascripti del comun di Chirignago diseno tutti a una voce che, se avesseno veduto lo dicto instrumento parlase cusì chiaro, mai averebeno dicta parola e che erano contenti de relasare lo dicto boscho al dicto monastero.53«And so all the men of the Commune of Chirignago said loudly that if they had seen the document before, which spoke so clearly, they would never have said a word, and said they were happy to leave the said forest to the said monastery»: ASVe, San Giorgio Maggiore, folder 72, trial 148, ff. without markings.

From the mid-fifteenth century onwards, there are numerous testimonies of disputes between Venetian abbeys over the boundaries established over productive lands located beyond Venice, in the nearby wetlands, and they are certainly nothing new in the context of northern Italy.54To learn more about the involvement of religious institutions in disputes concerning the use of uncultivated land and forests see Canzian, «I boschi della Repubblica». However, as regards the documentation considered here, it is interesting to note that, despite its heterogeneity from a documentary point of view, all the evidence on the disputed property (private deeds regarding boundaries, drawings, and expert reports), all converged within a single legal dossier, in which the disputed property continued to be accurately described over the years.55An analysis of the gradual build-up of this type of documentation, organised by «trials» can be found in Minotto, «Tra le carte dei monaci», 38-43. Its location, purpose, and possible physical or legal evolution were described, sometimes recounted through the testimony of witnesses56With reference to witness statements as an account of the territory, see Paolo Marchetti, «Spazio politico e confini nella scienza giuridica del tardo medioevo», Reti Medievali Rivista 7, no. 1 (2006): 8, https://doi.org/10.6092/1593-2214/2006/1. and, finally, its graphical representation was preserved, which helped to provide not only judicial but concrete and tangible evidence of the places.

We have two other testimonies of this way of working. The first dates back to 1455, on the occasion of the dispute that arose between the monasteries of San Cipriano di Murano and Santi Felice e Fortunato on the island of Ammiana, which has now disappeared. The dispute arose over a property near the mouth of the Dese River, located in the district of Mestre. The dispute had arisen as a result of the abusive action of a tenant of Santi Felice e Fortunato, who had encroached on some land beyond the borders established between the two owners during haymaking. The dispute was settled two years later, in 1457, in favour of the monks of San Cipriano. Prior to the final judgement, an inspection of the land in dispute was undertaken, «viso etiam loco differentiae ad quem personaliter accessimus», and a drawing was made, accompanied by three preparatory pen sketches that later became part of the court file.57See Emanuela Casti Moreschi and Elena Zolli, Boschi della Serenissima. Storia di un rapporto uomo-ambiente (Venice: Arsenale, 1988), 52-54. The reproduction of the map, from the Mensa Patriarcale archive collection, can be found in Casti Moreschi and Zolli, Boschi della Serenissima, 49.

In the second case, however, the site of the dispute was in the lagoon waters, where Venetian communities could extend the border of the space reserved for them beyond the land in order to make it productive. This was in fact a dispute over the boundaries of a fishing valley located in the lower waters of the southern lagoon, towards Chioggia. In the voluminous legal dossier attesting to the long dispute between the San Giorgio Maggiore and San Cipriano di Murano over the ownership of a fishing valley called San Marco Nuovo,58ASVe, Mensa Patriarcale, folder 92, trial 281, marked D (1485-1491). News about the San Marco Nuovo valley also appears in envelopes 112 and 89 of the collection, where there are also two drawings depicting the valley. we encounter a novelty: those who had to arbitrate the dispute considered it important to determine whether, before then, that same valley had been used as a salt marsh. But the boundaries and even the essence of the places were uncertain and changeable. Among the inhabitants or fishermen called to testify in the dispute, there were those who said they had always seen poles driven into the water in those areas, «palos affixos iuxere rippis canalis», as was usually the case with salt marshes; but there were those who, on the contrary, said they had never heard of salt «cultivation» being conducted there. Establishing that the valley had previously been used for the extraction of salt, meant affirming that the ancient feudal relationship of the livello contracts, which provided for the restitution of the goods to the owner, was in force on that property. This meant that during the court proceedings, the abbot of San Giorgio, in order to avert the loss of the valley, argued that the monks of San Cipriano had misplaced the geographic location of the disputed property and that there had never been any salt pans in the place where the valley was located. He also argued that, for these same reasons, the other party’s attempt to present deeds of donation of salt-pan foundations dating back more than three centuries from the time of the indictment should be considered useless; such deeds, he declared, could only refer to land assets other than those in dispute. Again, in the legal file, in addition to the testimonies, reference is made to the inspectio ocularis (‘the survey’)59With reference to the on-site inspection as a means of evidence to be used in conjunction with witness statements see Marchetti, «Spazio politico e confini», 8. and to the consequent graphic transposition of the area under investigation, that is, the drawing.60ASVe, Mensa Patriarcale, folder 112 s. d. Drawing published in Jean Claude Hocquet, «Histoire et cartographie. Les salines de Venise et Chioggia au Moyen Âge», Atti dell’Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti 128 (1969-1970): 549 (with provisional archival placement). Information on the same valley also in Claudio Grandis, «Le valli salse da pesca e da uccelli. Diritti e concessioni di spazi anfibi sospesi tra terra e mare», in Le valli. Storie e immagini tra Chioggia e Saccisica, ed. Claudio Grandis, Giampaolo Rallo and Pier Giorgio Tiozzo Gobbetto (s. l.: Peruzzo, 2009), 21-27, where the drawing of the San Marco valley, made in 1575 by the surveyor Ottavio Fabri on the occasion of the dispute that arose between the house of San Cipriano and Bortola Bognolo, is published, preserved in the same collection: ibidem, folder 89, 1575. The graphic representation of the disputed site thus became a fundamental evidentiary act to determine the reasons for ownership and the limits of use of the opposing parties.

Thus, having an ancient map at one’s disposal could be a winning factor in border disputes. Consider the case, dating back to the 1670s, of Sant’Andrea della Zirada, a Venetian convent that owned woods, lands, and meadows in the Venetian hinterland. In the dispute that arose between the nuns and the Commune of Carpenedo over the usurpation of a meadow located within a wood. The Commune denounced the nunnery’s tenant for using the wood and the meadow, for cutting wood and uprooting trees, and for ploughing and sowing in the aforementioned meadow, without having the authority to do so. In order to prove their property rights, the representatives of the Commune declared that they had some letters that could help settle the matter, but the nuns promptly played their card. During the deposition, the abbess, in defence of the rights and ancient prerogatives of her nunnery, declared that she had previously shown the representatives of the Commune a drawing, which attested to the community’s patrimonial rights over those lands and which should have convinced the men of Carpenedo to desist from the dispute. She also emphasised the relevance that, in her opinion, this map should have had in the immediate resolution of the border dispute:

Credevimo noi povere monache di Santo Andrea di Zirà de Venetia che li intervenienti per il Comun di Carpenedo, veduto l’antichissimo dissegno per noi presentato, dovessero totalmente acquietarsi et non ci dare altra molestia sopra i luochi nostri et tanto più quanto che già son nove mesi che gli lo presentassimo, ne da impòr hanno avuto ordine d’aprir bocca. Ma poiché doppo tanto tempo gli è tornato il spirito di contraddizione, onde con nove scritture et cavillationi ci travagliano indebitamente, gli diciamo di novo anchor noi che se vorranno ben considerar il nostro dissegno, fatto già tante decine d’anni, si chiariranno che il fosso che si vede fra il nostro et il suo boscho […] rende non di meno vestigio di lui chiaro et indubitato […] ad ognuno che lui si divideva et separava il nostro dal suo […].61«We poor nuns of Sant’Andrea della Zirada in Venice believed that the claims put forward by the Commune of Carpenedo, in view of the very old design we presented, should be completely settled and that the representatives of the Commune should not give us any more trouble on our premises, especially as we presented the drawing to them nine months ago, and on that occasion they made no other requests. However, since after such a long time they have wanted to resume the controversy, for which they continue to torment us with writings and pretexts, we say and repeat once again that if they want to look at our drawing, which was made many decades ago, they will see that the ditch that can be seen between our forest and theirs clearly and unquestionably represents the ancient boundary that separated our land from theirs»: ASVe, Sant’Andrea della Zirada, Deeds, folder 15, file 29, ff. 17-18.

5. CONCLUSIONS

⌅Thanks to recent acquisitions on the theme of medieval frontiers, this work proposes to comparatively read data from some monastic case studies in order to verify the existence of common practices of intervention on the territory in frontier geographical contexts in the northern area of the Italian peninsula.62Reference is made to the already mentioned Abulafia, «Introduction»; and Constable, «Frontiers».

The borders we have dealt with are defined as internal limits of geographical regions and as markers of local political and environmental interactions; the natural environment and its resources have in fact deeply conditioned the creation of the borders we have analysed. Crucial in this process is the role played by environmental, natural and anthropic modifications, sometimes very rapid and profound, in the transformation of the borders themselves. Such transformations often caused a widespread legal uncertainty on the limits of the spaces within which people, monks and institutions could act. At the same time, the condition of uncertainty gave the most resourceful landowners the opportunity to secure, through usurpation, a personal certification or invention of new inclusive or exclusive boundaries.

The choice of comparing different geographical environments, which was mentioned at the beginning, is part of a broader scientific perspective of reconstruction, both in a chronological and comparative sense, of the environmental and landscape layout of important sectors of the medieval Italian countryside. This reconstruction entails analysing the methods of boundary and its reconfiguration, the practices used to describe the borders and the spaces gravitating around the borders, as well as the technical acquisitions that were gradually formed around these practices.

The monastic world is central in research on medieval landscapes, precisely because, within all the documentation produced in this context, there is a synthesis of the multiform variety of both private and public interests connected with the knowledge, description, and transformation of the environment. On the one hand, the Carthusian and Cistercian communities in the mountains and plains of northern Italy, in their pursuit of isolation, initiated a process of territorial modification in accordance with a long-term project of expansion of monastic property, expanding the boundaries over ever larger areas of territory, ousting outsiders as far as possible and creating ex novo territorial areas capable of offering —in environmental terms— greater resources and more opportunities to make the land productive. In the process of appropriating territory, the practices of boundary demarcation, realised through the manipulation of natural signs (trees, waterways, artefacts, etc.), and their reinterpretation using a precise legal status, constituted a fundamentally important step.

However, along the Venetian lagoon margins, in a peculiar hydrogeological, settlement and land context, the organisation of the space outside the cloisters depended on an almost impossible environmental and jurisdictional balance to be sought in conditions of extremely high instability: amidst terrain that continually changed its appearance due to the action on them of fresh and salt water, as well as resettlements always of an uncertain and disputed nature. These opposing thrusts required continuous work of delimitation and re-bordering, formalised through constant verifications and measurements. What makes these operations (tirelessly repeated over time) an extraordinary factor of concrete knowledge of the territory for the men and women of the time is the centrality assumed by the surveys of the technicians and the production of a particularly numerous and detailed cartography of the areas surveyed.

From the thirteenth century onwards, attempts to conquer new land also multiplied in all the areas which have been taken into consideration here. In Carthusian alpine valleys such as Cistercian Padana plain, up to the margins of the lagoon, the monks continued the intense and meticulous work of enlarging/extending and consolidating of the boundaries of their properties following the numerous purchases of land. The hermits of Pesio settled also in the plain where they founded new cereal granges; the Colomba Cistercian monks started a recovery and reorganization effort of their properties which had been severely impoverished during the mid-century wars of Friedrick II.63Anna Rapetti, La formazione di una comunità cistercense. Istituzioni e strutture organizzative di Chiaravalle della Colomba tra XII e XIII secolo (Rome: Herder, 1999), 269-278. This process occurred also in the city of Venice and the islands of the lagoon, on the basis of a conscious project of expansion of the urban fabric consistent with the expansion of monastic property. Indeed, there is no lack of evidence of interventions to redefine and demarcate those lagoon areas of the coenobia that were located within the built-up area of Venice. For instance, beginning with the numerous plots of marshy land owned in the Dorsoduro district in the last quarter of the eleventh century, the ancient coenobium of Sant’Ilario promoted, in the thirteenth century, intense work of reclamation and urbanisation of the islet of San Gregorio, which in the twelfth century was still largely occupied by quagmires for hunting and by abandoned salt works. This small island changed completely in less than a century, becoming an integral part of the urban fabric.64Anna Rapetti, «Il doge e i suoi monaci. Il monastero dei Santi Ilario e Benedetto di Venezia fra laguna e terraferma nei secoli IX-X», Reti Medievali Rivista 18, no. 2 (2017): 20, https://doi.org/10.6092/1593-2214/2017/2.

The acquisition of new lands and the consequent conflicts with neighbouring owners made borders increasingly contended, which in turn made it necessary for public power, judicial authorities, and specific technicians (such as the perticatori in the Venetian case) to intervene. The monks continued to transform the surrounding space, but the context in which they acted in the last centuries of the Middle Ages had become profoundly different.65Fiorenzo Landi, Il paradiso dei monaci. Accumulazione e dissoluzione dei patrimoni del clero regolare in et à moderna (Rome: La Nuova Italia Scientifica, 1996). The political and administrative structure of the territories was consolidating within the frame of the emerging regional states, while competition between old and new landowners was increasing, with the latter often having large capital to invest in improvements and infrastructure at their disposal. Out of either necessity or choice, the monks re-oriented their action especially towards the border areas characterized by uncultivated productive terrains and the swamps, still present along the numerous rivers in the Padana plain that flowed into the sea.66Cf. Gianmario Guidarelli and Elena Svalduz, «Valore storico, economico e sociale delle bonifiche in età moderna», in Acqua e terra nei paesaggi monastici. Gestione, cura e costruzione del suolo, ed. Dario Canzian and Giovanna Valenzano (Padua: Padova University Press, 2022), 133-134; Simonetti, Da Padova a Venezia, 139. On these marginal lands, they generated the conditions to start farming and exerted more careful surveillance of the borders.